by Laurence Teillet[1]

Published in Environmental Rights Review 1(1) 2023

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8301855

Download PDF here:

Abstract: Human rights law emerged in the 19th century in a Westphalian international community characterized by sovereign States. This new area of law revolutionized the legal order. It asserted the importance of the human being, regardless of nationality, as a bearer of specific rights defined by the international order. This emerging philosophy gave rise to a new doctrine: the doctrine of humanitarian assistance. In turn, this doctrine led to the concept of the Responsibility to Protect (R2P). The legal basis of R2P and its relevance remains controversial. However, most scholars agree that R2P has a normative quality, whose basis lies between morals and legality.

Initially, R2P appeared to have little connection to environmental issues. R2P could only be invoked in major humanitarian disasters constituting international crimes under the Statute of the International Criminal Court (ICC): genocide, crime against humanity, crime of aggression, and war crimes. However, recent legal scholarship has underscored the connections between human rights and environmental health. One example is the growing recognition of the human right to a healthy environment. This right has been recognized in many countries and acknowledged by the United Nations Human Rights Council in Resolution 48/13 (2021) and the United Nations General Assembly in Resolution 76/300 (2022). There is mounting evidence suggesting this right is customary.

Building upon these developments, this paper argues that breaches of the right to a healthy environment, if they amount to international crimes as defined in the ICC Statute, could serve as the basis for activating R2P. The right to a healthy environment includes an emphasis on mental health. While this argument previously may have been deemed unreasonable, recent developments on the crime of ecocide and requests to the Office of the Prosecutor of the ICC to investigate Jair Bolsonaro’s alleged destruction of the Amazonian Forest as a crime against humanity offer compelling evidence of the evolving legal scholarship on this subject.

I. Introduction

On 28 July 2022, the United Nations General Assembly (UNGA), in a historical decision, officially recognized the right to a clean, healthy, and sustainable environment as a fundamental human right.[2] This recognition built upon the efforts of the United Nations Human Rights Council (UNHRC), which had already recognized the right to a healthy environment in 2021.[3] The UNHRC resolution was the first milestone in an ongoing process of solidifying this right, further strengthened by the UNGA resolution. The UNGA resolution was overwhelmingly supported: 161 States voted in favor of this right, and only eight countries abstained.[4] This recognition solidified the inseparable link between human rights and environmental protection, affirming that they are two sides of the same coin.[5] In January 2022, Marc Limon, the Executive Director of the Universal Rights Group and a former diplomat at the UNHRC, provided a firsthand account of the UN’s recognition of the universal right to a clean, healthy, and sustainable environment.[6] Limon highlighted two crucial questions requiring further exploration.[7] One such question pertains to the extent of States’ obligations to promote, protect, and respect this newly recognized right to a healthy environment beyond their own borders.[8] This raises the question of the right’s enforcement, and whether it has extraterritorial implications.[9]

Human rights law emerged in the 19th century in a Westphalian international community characterized by sovereign States.[10] This new area of law revolutionized the legal order: it asserted the importance of the human being, regardless of nationality, as a bearer of rights defined by the international order.[11] This emerging philosophy gave rise to a new doctrine: the doctrine of humanitarian assistance. In turn, this doctrine led to the concept of the Responsibility to Protect (R2P).[12] The legal basis of R2P and its relevance may be questioned. However, most scholars agree that R2P has a normative quality, whose basis lies between morals and legality.[13]

Initially, the R2P appeared to have little connection to environmental issues. R2P could only be invoked in major humanitarian disasters constituting international crimes under the Statute of the International Criminal Court (ICC): genocide, crime against humanity, crime of aggression, and war crimes.[14] However, recent legal scholarship has underscored the connections between human rights and environmental health. One example is the growing recognition of the human right to a healthy environment, as shown above by the UNHRC and UNGA and in States’ domestic systems.[15] There is mounting evidence suggesting this right is customary.[16]

Building upon this understanding, this paper argues that breaches of the right to a healthy environment, if they amount to international crimes as defined in the ICC Statute, could serve as the basis for activating the R2P. This article, first, explores the emergence of the doctrine of humanitarian assistance and its evolution into R2P, emphasizing the shared international duty to respect, protect, and enforce human rights. Second, it examines the prevalence of human rights and anthropocentric interests within the rationale of R2P and discusses the relevance of environmental concerns in this framework. Third, it highlights the interconnection between the protection of human rights and the preservation of the environment, as exemplified by the recognition of the right to a healthy environment. Finally, it considers the possibility of activating R2P in cases of severe environmental degradation.

II. The Transition from Humanitarian Assistance to R2P: Human Rights Protection as a Collective Duty

R2P is not a recent concept, but it has gained popularity or formalism in the last decades.[17] Originally conceived to prioritize the protection of individual human integrity, R2P was sometimes presented as a right of interference or humanitarian interventionism.[18] R2P is not explicitly recognized by international humanitarian law (IHL). However, theories of humanitarian assistance and later R2P emerged from the new vision of the international order brought by the development of IHL.[19] These theories reject an absolute interpretation of a State’s sovereignty. They incorporate a moral component into international law, which prioritizes the protection of the human individual as an ultimate and unquestionable objective.[20] These concepts raise questions about their legality, legitimacy, interactions, and respective pitfalls. Humanitarian assistance and R2P aim to address grave human rights violations enabled by absolute State sovereignty. However, their main limitation is the risk of subjectivity and neo-colonialism by powerful States seeking to impose their own vision of society and human rights.[21] This pitfall was initially supposedly mitigated by the principle of State sovereignty, creating a perpetual quest for the perfect balance.[22]

The principles of sovereignty and sovereign equality hold central positions in international law. Derived from these principles are two crucial rules: the principle of non-interference and the prohibition on the use of force.[23] Interference refers to any act disrupting a State’s internal affairs, even without the use of force.[24] The principle of non-intervention encompasses similar acts but involves the use of force.[25] These principles are considered cornerstones of the United Nations (UN) Charter and have gained customary status since the International Court of Justice’s (ICJ) 1984 decision on the Military and Paramilitary Activities in and Against Nicaragua.[26]

The prohibition on the use of force in international law is not absolute. Using force can notably be authorized by the UN Security Council when a threat to peace, breach of peace, or act of aggression is recognized, per Article 39 of the UN Charter.[27] Chapter VII of the UN Charter outlines the process for triggering coercive action by the United Nations.[28] However, the powers of the UN Security Council is regulated. Its actions must comply with jus cogens norms and align with the values and objectives of the organization.[29] Nevertheless, these safeguards have limitations, and the legitimacy of the UN Security Council is subject to vigorous debate: only 15 States have a seat, with five holding permanent seats and a right to veto decisions which are not procedural matters.[30] As a result, authorizing the use of force in international law falls short of an egalitarian and democratic process.[31]

Discussions advocating for forms of humanitarian assistance without the agreement of the target State emerged in the 1980s. For instance, UNGA Resolution 43/131 reaffirmed States’ territorial sovereignty while emphasizing that non-governmental associations with purely humanitarian purposes could intervene in situations of natural disasters or similar emergencies.[32] This left the door open to various eventualities. Initially, States and international organizations were excluded from the application of this emerging doctrine of humanitarian assistance, but were progressively included from the 1990s onwards.[33] In 1991, the UNGA called on States to participate in humanitarian assistance efforts in Iraq. Notable and contested responses came from France, the United Kingdom, and the United States.[34]

A lexical change took place in the mid-1990s when the doctrine of humanitarian assistance gradually transformed into a “responsibility to protect”.[35] Although this change may appear minor, its consequences are significant.[36] The shift from humanitarian intervention to R2P implies a major change in doctrine. Humanitarian intervention is discretionary and does not involve any obligation. Meanwhile, R2P entails a shared responsibility, where the focus shifts from whether to respond to how to respond.[37] R2P emerged as a response to the international community’s failures in preventing mass atrocity crimes of the later 20th century, such as the Rwandan genocide in 1994.[38] The International Commission on Intervention and State Sovereignty (ICISS) was established in 2000 to clarify the meaning and criteria of the R2P.[39] According to the ICISS’ report, R2P can only be invoked in situations of humanitarian disasters involving international crimes as defined in the ICC Statute, and the State invoking R2P must have a just intention.[40] Additionally, intervention must be the last proportional and reasonable option to stop human rights violations.[41] The ICISS outlined three types of responsibilities: reaction, protection, and rebuilding.[42] This paper focuses on R2P, which involves intervention in a target State.

Despite these clarifications, R2P has not received widespread acceptance.[43] Yet, its recurrence in public and legal discussions underscores the enduring relevance of this concept. The UN Special Adviser on the Responsibility to Protect has asserted its normative quality, and the 2005 World Summit Outcome recognized the responsibility to protect populations from genocide, war crimes, ethnic cleansing, and crimes against humanity.[44] This exact formulation differs from the one suggested by the ICISS, but the substance remains similar, and it does not deny the reference to the R2P concept.[45] However, the World Summit Outcome is not binding, and the customary status of R2P remains debatable given the absence of convincing State practice and opinio juris.[46] Nevertheless, R2P has served as the legal basis for several international interventions, albeit in theory subject to the authorization of the UN Security Council.[47]

In recent years, the linkage between human rights and environmental law has become increasingly evident. This suggests that R2P should be broadened to include concerns beyond anthropocentric interests, including environmental protection.

III. Assessing the Relevance of the Environment in R2P

There can be no doubt that the provision of strictly humanitarian aid to persons or forces in another country, whatever their political affiliations or objectives, cannot be regarded as unlawful intervention, or as in any other way contrary to international law (emphasis added)[48]

As early as 1986, the ICJ seemed to support the idea of external intervention or interference, but solely for the purpose of providing humanitarian assistance.[49] As will be seen, the connection between the environment and human rights is strengthening. However, the ICC Statute makes almost no direct reference to ecological disasters or environmental concerns.[50] While the ICISS report mentions ecological and natural disasters, it does so only in the context of their impact on human rights.[51]

Legal scholarship has also expressed hesitation about expanding the scope of R2P to the environment. Malone, who created the notion of ‘ecological interventionism’, wrote in 2009: “We need to be very cautious about even considering the idea of extending the reach of the responsibility to protect norm to environmental emergencies”.[52] Two reasons justify this reservation about a responsibility to protect the environment, as disconnected from anthropocentric interests.

First, the criteria of R2P are incompatible with such an idea. The requirement of “just intention” means that States contemplating intervention must not have ulterior motives. Instead, they must be guided solely by the intention to halt the humanitarian disaster that justifies the initial action.[53] However, the “just intention” criterion does not demand that the motives be absolutely pure — as legal doctrine recognizes the impracticality of such a requirement.[54] Scholars argue that “just intention” should be interpreted as akin to a “good will” obligation: the primary objective is to effectively prevent human rights violations.[55] Other motives are not forbidden, but must remain secondary.[56] Consequently, if an intervention were to be allowed for secondary environmental motives, the primary justification for such intervention must still be to protect and preserve human rights.[57] Furthermore, the intervention must be the last reasonable and proportionate resort to address the human rights violation.[58] Hence, the original text of R2P makes this framework challenging for addressing purely environmental problems.

Second, while human rights protection is largely consensual in international law, environmental protection, unfortunately, remains more problematic and controversial. Denial of climate change aside, past cases in which environmental protection was invoked as a motive have made several States cautious about international action on environmentalist grounds.[59] One recurring criticism from target States is the issue of subjectivity.[60] One example is the Whaling case, where Australia and New Zealand opposed Japan before the ICJ.[61] Australia accused Japan of continuing commercial whaling activities, despite the moratorium imposed by the International Whaling Commission, by disguising whaling as scientific research.[62] Although Australia did not suffer direct harm from these activities, it invoked the protection of erga omnes obligations and the common interest.[63] The ICJ accepted Australia’s argument and recognized the erga omnes character of the moratorium.[64] However, identifying a rule as erga omnes has implicit consequences. It implies that the obligation in question protects fundamental moral values which are upheld globally.[65] However, considering the commercial whaling moratorium as having fundamental moral value with worldwide consensus poses problems of acceptability. Whaling was a marginal activity for many Western countries. Yet, it was a significant economic activity for Japan and other whaling nations, like Norway and Iceland.[66] Japan’s historical and cultural attitudes toward whales, shaped by its long history of whaling and consumption of whale meat, limited Japan’s recognition of whales as creatures deserving of special protection.[67] Consequently, prioritizing the protection of whales over other species was seen as unjustified and biased from an ecological standpoint.[68] Moreover, it made Japan more hesitant about international environmental regulations concerning fisheries and marine resources.[69] Following the Whaling case, Japan rejected the jurisdiction of the ICJ for all disputes related to these topics.[70] This example is not directly linked to the R2P. However, it demonstrates the unease that interference based on environmental protection has already caused in several States. Therefore, legal scholars believe that developing R2P to extend to the environment could elicit stronger resistance from States compared to the current reactions to human rights protection.[71]

Nevertheless, one need to nuance the conclusion that the R2P has no connection to environmental preservation on two grounds. First, legal doctrine has shown on numerous occasions that R2P could be invoked in environmental emergencies if specific requirements are met.[72] For instance, R2P could be considered in an environmental emergency, where the target State’s response or lack of response could amount to a international crimes – therefore meeting the thresholds for the R2P’s activation.[73] The case of Cyclone Nargis in Myanmar is often cited as an example. Some argued that the actions of the Myanmar government during the cyclone amounted to a crime against humanity, prompting a potential intervention based on the R2P principle.[74] In this case, the Myanmar government’s failure to take action in response to the environmental catastrophe resulted in significant degradation, which had a profound impact on human rights.[75] The level of inaction raised the possibility that the government’s failure to protect the environment could be considered a crime against humanity given its sustained impact on the local population.[76] More recently, the ICC expressed its intention to investigate environmental damages.[77] Similarly, Chief Raoni Metuktire of the Kapayo Indigenous group in Brazil has accused Jair Bolsonaro of crimes against humanity for the destruction of the Amazonian Forest and Indigenous lands in a request to the Office of the Prosecutor of the ICC.[78] However, even if a crime against humanity were to be established in a particular case, international intervention would still be primarily based on the protection of human rights, the protection of the environment in environmental emergencies would be a collateral benefit.[79] Second, as will explored in the next section, the interdependence between human rights protection and environmental preservation is growing stronger. Consequently, two issues once seen as separate and sometimes even in competition are now increasingly understood as interconnected. This realization may encourage us to reconsider the initial pessimistic conclusion on the links between R2P and the protection of the environment.

IV. Exploring the Interplay between Human Rights and Environmental Protection in the Right to a Healthy Environment

In his account of the United Nations’ recognition of the universal right to a healthy environment, Marc Limon highlighted the initial belief held by most States that the protection of human rights and the preservation of the environment should remain separate.[80] However, empirical studies have long shown a correlation between increased social welfare and environmental degradation.[81] O’Neill et al. conducted a study on nearly 150 States, which demonstrated that “the more social thresholds a country achieves, the more biophysical boundaries it transgresses, and vice versa.”[82]

Some scholars argue that separating human rights concerns from environmental protection is illogical.[83] They believe distinguishing between the interests of humankind and the protection of nature is illogical as the two are inherently interconnected.[84] Our world functions as an integrated system, safeguarding human rights necessitates environmental protection.[85] This perspective resolves potential theoretical conflicts between human rights and environmental preservation. While it may sound idealistic, non-Western legal traditions have long implemented such a vision. For instance, Sharia Law considers humans as superior to other species due to their ability to reason (‘aqal), but humans are seen as dependent on other living creatures and the overall environmental health.[86] Although this perspective is gaining popularity, the merging of human and environmental interests remains on the periphery of international law.[87] Today, States typically continue to discuss interlinkages and a common core between human rights and environmental protection rather than completely integrating both.[88]

One of the most compelling evidence of the link between human rights and the environment is the development of the human right to a clean, healthy, and sustainable environment.[89] Intrinsically tied to the right to life and the right to health, the right to a healthy environment has been gaining recognition in the international legal order. This is thanks to a cautious and gradual approach employed by diplomats from a few countries.[90] The first mention of the right to a healthy environment at the international level occurred in the 1972 Stockholm Declaration. It recognized that humans “have the fundamental right to freedom, equality, and adequate conditions of life, in an environment of a quality that permits a life of dignity and well-being.”[91] The 2021 UNHRC resolution and the 2022 UNGA resolution both acknowledge the right to a clean, healthy, and sustainable environment as a fundamental human right interconnected with existing international law and other rights.[92] The resolutions insist on the importance of implementing international environmental law and urge States, international organizations, businesses, and stakeholders to enhance global cooperation in achieving this objective.[93] The resolutions express the significance of the right to a healthy environment. However, they provide limited clarification on the precise interpretation and scope of its terms. Therefore, examining the interpretations of other UN bodies and academic literature is necessary to gain a fuller understanding of this right.

First, the right to a healthy environment is anthropocentric. It centers around human health and how human health can be affected by the state of the environment — rather than the other way around.[94] Second, the term “health” is interpreted broadly. According to the World Health Organization’s definition, “health is a state of complete physical, mental, and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity.”[95]

At first glance, the connections between environmental health and human health are more straightforward when the consequences of environmental degradation directly affect people’s physical well-being, as seen in cases of natural disasters, like Cyclone Nargis.[96] For slower-onset phenomena, including climate change, legal precedents are rapidly emerging which demonstrate the relationship between environmental health and human health when there are tangible physical impacts.[97] For instance, over 2,000 women have initiated legal proceedings against the Swiss government before the European Court of Human Rights, alleging that its climate change policy is infringing upon their right to a healthy environment.[98] Referred to as the Club of Climate Seniors, these women have an average age of 73 and argue that climate change poses risks to their human rights, health, and even lives.[99] Their medical records are evidence in the case.[100] As a result of climate change, the frequency of heatwaves has increased, which disproportionately impacts older women who are more vulnerable to such extreme temperatures.[101] Consequently, these women face a higher mortality rate during heatwaves compared to other circumstances.[102] The verdict of this case centered on personal physical risks stemming from climate change is yet to be determined. Yet, the links between climate change and threats to a population’s physical health are well-documented.[103]

The non-physical consequences of environmental degradation, such as mental health effects, also deserve consideration. These impacts are more complex to define due to their subjective nature, the difficulty of establishing a causal link, and the challenges in observing and demonstrating them. Nevertheless, this paper argues that mental health impacts can serve as a catalyst for incorporating environmental protection in a wider range of cases, even potentially in the most severe cases which could activate R2P. Indeed, demonstrating physical consequences of environmental degradation, whether currently in the future, can often be challenging. Many harmful projects or policies may not immediately result in tangible physical effects in the short or medium term.[104] However, environmental degradation can have a significant impact on the mental health of populations. This is despite safeguarding mental well-being is a part of the right to a healthy environment, as defined by the World Health Organisation.[105]

Recent research in psychology and public health has revealed new mental conditions directly linked to environmental degradation.[106] Two of the most discussed conditions are eco-anxiety and solastalgia (also known as econostalgia).[107] Eco-anxiety refers to fear and anxiety related to climate change and environmental degradation, focusing on anticipated negative changes in the future.[108] Eco-anxiety is associated with experiences of frustration, powerlessness, fear, anger, and exhaustion.[109] Solastalgia, a term coined by Albrecht in 2003, describes a sense of grief and mourning for what has already been lost due to climate change and environmental destruction.[110] Solastalgia highlights risks of triggering identity crises associated with changing landscapes and the consequent disappearance of traditional means of subsistence, such as farming and fishing, due to climate change.[111]

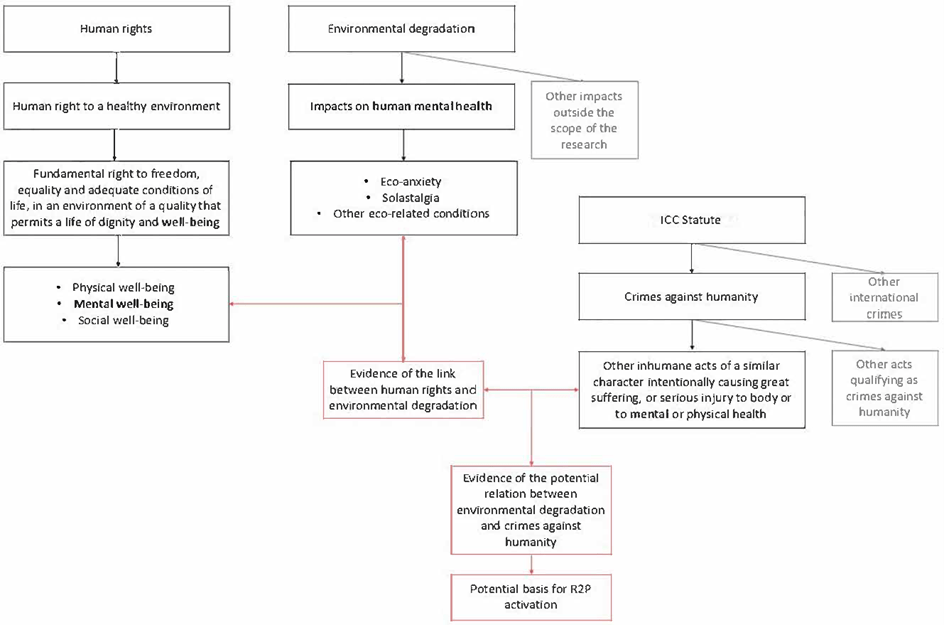

Research demonstrates that climate change can significantly impact mental well-being, leading to consequences such as depression, post-traumatic syndrome, emotional distress, and suicidal thoughts or attempts.[112] For instance, recent studies reveal a direct increase in suicide rates amongst farmers in India due to the climate crisis.[113] Conditions specifically related to the environment, such as solastalgia and eco-anxiety, have not been officially recognized in psychiatric diagnostic manuals, like the ICD-10 and DSM-5. However, the consequences of these conditions, such as post-traumatic stress disorder, is documented.[114] Consequently, any form of environmental degradation that contributes to mental health issues could be considered a breach of the human right to a healthy environment. As depicted in Diagram 1, if the right to a healthy environment guarantees mental well-being, any form of environmental degradation leading to eco-anxiety or solastalgia could be deemed a violation of this human right.

Diagram 1: Representation of the links between human rights and environmental degradation through the right to a healthy environment.

Despite growing discussions around the mental health implications of environmental degradation, one must be cautious before drawing conclusions and inferring legal consequences for this connection. Albrecht’s contributions to interdisciplinary scholarship are significant and his research on solastalgia has paved the way for a new field of study. However, Albrecht is an environmental philosopher, not a psychologist or psychiatrist.[115] Clinical studies on the impacts of environmental degradation on mental health are still limited.[116] The current consensus is that, although there is “substantial reason for concern” about the psychological effects of gradual changes in the climate and the environment, further clarity and theoretical development of the concepts of eco-anxiety and solastalgia are necessary.[117]

The following developments are, therefore, presented for theoretical exploration. They remain contingent upon the advancement of studies on the recognition of the normativity and legal implications of the right to a healthy environment, the emergence of new clinical research reinforcing the connections between environmental degradation and human mental health, and the establishment of definitive causal link between environmental degradation and the emergence of these mental health conditions. Although these claims may not be currently legally tenable, they reflect a widely held belief amongst environmental activists that protecting the environment and its inhabitants is crucial for human rights.[118] With the progressive development of human rights influenced by environmental health, they may gain stronger legal and ethical backing in the medium to long term and, as such, deserve further legal study on their potential consequences.

V. The Right to a Healthy Environment and Crimes Against Humanity: Unravelling the Implications and Criteria for R2P Activation

Drawing on the connections between the right to a healthy environment and R2P, this section demonstrates how the recognition of the right to a healthy environment can expand the R2P’s environmental dimension. Specifically, it explores how cases of crimes against humanity, in occurrences of intentional, widespread, and systematic attacks on the environment, could activate R2P.

As mentioned earlier, R2P is typically invoked in cases involving international crimes, as outlined in the ICC Statute.[119] The ICC Statute encompasses four core crimes: genocide, crime against humanity, war crimes, and the crime of aggression.[120] If environmental degradation meets the criteria of any of these crimes, R2P could be activated within the context of environmental protection.

Amongst these international crimes, crimes against humanity are particularly relevant to this study. They encompass acts committed as part of a widespread or systematic attack directed against a civilian population where the perpetrator knows that the conduct was part of or intended the conduct to be part of a widespread or systematic attack directed against a civilian population.[121] Article 7 of the ICC Statute provides a comprehensive list of acts that could qualify as crimes against humanity.[122] It notably prohibits “crime against humanity of other inhumane acts” as acts that cause great suffering or serious injury to body or to mental or physical health by means of an inhumane act.[123] Such act must be of a character similar to other acts constituting crimes against humanity. This provision underscores the ICC Statute’s recognition of the importance of safeguarding populations’ mental health in the context of crimes against humanity.

As shown previously, the right to a healthy environment highlights the impact of environmental degradation on the mental health of populations. Consequently, in certain circumstances, if environmental degradation affects mental health, it may be considered as a factor in recognizing crimes against humanity, thereby providing a basis for invoking R2P. The following diagram illustrates these interlinkages.

Diagram 2: Illustration of the links between the right to a healthy environment, mental health protection, crimes against humanity, and R2P.

However, specific conditions must be met for this recognition:

- A widespread or systematic attack against the environment must occur, with an awareness of the mental health consequences for the affected population.[124] Given the links between environmental protection and observance to human rights, it may be that a widespread or systematic attack against civilians may, in specific instances, amount to a widespread or systematic attack against the environment.

- The perpetrator must have known that their actions formed part of, or were intended to be part of, a widespread or systematic attack against the environment.[125]

- Multiple acts must be committed, as crimes against humanity require a pattern of conduct.[126]

- The commission of the acts must be pursuant to or in furtherance of a State or organizational policy to commit such attack.[127]

- The mental health impacts on the population must reach a threshold of “great suffering” or “serious injury”.[128] Minor mental health impacts would not qualify as crimes against humanity. The gravity of the mental health impact should be comparable to other acts constituting crimes against humanity, such as persecution, enforced disappearance of persons, apartheid, sexual slavery, or rape.[129]

Once crimes against humanity are legitimately suspected, additional criteria must be fulfilled for the activation of R2P:

- The intervention must have a “just intention”, which primarily aims to address the human rights violation — in this case, the mental health impacts resulting from environmental degradation.[130] By extension, the intervention would involve putting an end to the environmental harm causing such impacts.

- The intervention should be the last reasonable and proportionate resort available to effectively address the human rights violation.[131] This criterion emphasizes the importance of exhausting all diplomatic, non-coercive, and peaceful means before considering intervention. Despite the challenging thresholds, particularly concerning mental health impacts, which are often overlooked in prioritization, meeting the criteria of proportionality and necessity becomes feasible under specific circumstances.[132] For instance, consider the possibility of devastating wildfires that have been left unaddressed, not posing an immediate threat to human lives, but wreaking havoc on ancestral lands or critical ecosystems. Inaction in such a scenario could be viewed as unjustly affecting the mental health of local populations, justifying the intervention of third-party States to extinguish the wildfires in case diplomatic negotiations are unsuccessful.[133]

- If the ICISS guidelines are to be followed, the intervention would require approval from the UN Security Council.[134] However, as noted, the ICISS report is non-binding and cannot be considered as representing customary international law due to the lack of consistent State practice and opinio juris.[135]

The threshold for establishing a crime against humanity linked to environmental degradation and activating R2P on this basis is extremely high. The complexities in proving mental health impacts would further a particular hurdle. However, this high threshold may, in fact, have positive implications when considering the consequences and ramifications of invoking the R2P. While difficult, meeting this threshold is not theoretically impossible.

As the world continues to evolve, in the face of climate change, the discourse surrounding environmental R2P will undoubtably intensify in the years to come. Indeed, there have already been observable indications of its emergence. On 22 August 2019, when confronted with the devastating wildfires engulfing the Amazon rainforest, which posed a grave threat to ecological equilibrium, French President Emmanuel Macron emphasized the international significance of this crisis and the collective responsibility to address it.[136] He underscored the vital role played by the Amazon ecoregion in climate balance and the importance of these lands for Indigenous communities.[137] In response, the Brazilian government swiftly labelled Macron’s statement as evoking an “outdated colonialist mentality” and denounced it as interference.[138]

Nevertheless, numerous legal experts, journalists, and editorial writers have advocated for developing a genuine right to ecological interventionism.[139] For instance, Petite, recently argued that national sovereignty cannot be absolute and that, when a State fails in fulfilling its fundamental obligations towards the environment, the international community bears a subsidiary responsibility.[140] The notion of ecological interventionism is gaining traction and warrants careful consideration e to prevent conflicts, define its limitations, and ensure a peaceful approach to environmental protection. As the international community already recognizes environmental protection as a shared concern of humanity, address this evolving concept of environmental R2P is imperative.

VI. Conclusion

The International Panel of Eminent Personalities referred to the Rwandan Genocide as a “preventable genocide” in their 1994 report on this humanitarian catastrophe.[141] This genocide unfolded in Rwanda over a period of 100 days in 1994 and was characterized by a deliberate and systematic campaign of mass murder.[142] Extremist factions within Rwanda’s majority Hutu population orchestrated the genocide with the aim of targeting the minority Tutsi population and anyone who opposed their genocidal intentions.[143] This genocide resulted in the death of over 800,000 civilians, primarily Tutsi, and the displacement of 2,000,000 individuals who fled Rwanda during or immediately after the genocide.[144] In the aftermath, the international community acknowledged its own inaction and shared responsibility for the massacre through subsequent investigations.[145] This traumatic episode played a pivotal role in shaping the concept of R2P, which emerged as a means to prevent such catastrophic events from recurring.[146]

Is it necessary to wait for a catastrophic and traumatic environmental event to prompt the international community to consider a form of environmental assistance or R2P for the environment? This question is deliberately provocative, but demonstrates the need for further examination of this concept. In the absence of a specific legal regime, various international law concepts can offer valuable insights into how the international community could address environmental emergencies. This paper has highlighted the recent recognition of the right to a healthy environment by the UNHRC and UNGA, which could broadens the scope of environmental considerations.[147] The right to a healthy environment encompasses not only the protection of individuals from the physical impacts of environmental degradation, but also the mental health impacts.[148] By considering mental health impacts, a wider range of cases involving the environment can be considered. Many projects or actions that harm the environment may not directly affect the physical wellbeing of populations but instead have diffuse and gradual effects.[149]

Emerging literature suggests that severe mental health conditions can arise from environmental degradation, with eco-anxiety and solastalgia being two commonly discussed conditions.[150] While additional clinical studies are needed to fully understand the scope of these concepts, there is already evidence of the profound impact of climate change on mental health, as exemplified by the study of Indian farmers experiencing an increasing suicide rate.[151]

The focus on mental health, as influenced by environmental degradation, could open the door to considering environmental degradation as a qualifying factor, albeit under strict and restrictive conditions, for crimes against humanity. Indeed, the ICC Statute explicitly defines crimes against humanity as including inhumane acts that intentionally cause great suffering or serious injury to body, mental or physical health.[152] This paper recognized the significance of mental health within the framework of the ICC Statute and the established connections between environmental degradation and profound mental conditions. Consequently, it follows that environmental concerns could be considered when addressing crimes against humanity. The recognition of the right to a healthy environment strengthens this argument further. Although the current conditions for activating R2P are stringent, they are not unattainable. A noteworthy example is the request made by the Kapayo Indigenous group in Brazil to the ICC Office of the Prosecutor against the environmentally destructive policies of Jair Bolsonaro in the Amazon, which poses a threat to the livelihood, culture, and mental well-being of indigenous populations.[153]

If environmental harm can give rise to cases of crimes against humanity under strict circumstances, R2P could then be triggered where additional criteria are satisfied.[154] This would open the door to considering environmental protection as a shared interest transcending borders in extreme cases. However, it is important to recognize that the actual activation of R2P based on environmental harm remains contingent on numerous factors. Meeting all criteria is not impossible, but it is highly unlikely and exceedingly restrictive. Most instances of environmental harm, even severe ones, will not meet the threshold to trigger R2P, as they may not fulfil the necessary awareness, knowledge and/or intent requirements to qualify as a crime against humanity.[155] Furthermore, economic considerations often serve as partial justifications for actions leading to environmental degradation, even when the negative mental, physical, and social impacts on populations are well-known to decision-makers.[156] The prevailing Sustainable Development rationale prioritizes a permanent cost-benefit analysis, which tends to impede accountability for environmental harms.[157]

The future will bring further insights into the evolution of ecological interventionism. As the international community continues to study the connections between environmental degradation, mental health, and human rights, new developments in international law may emerge. The ongoing discussions surrounding the notion of ecocide, defined as unlawful or wanton acts committed with knowledge that there is a substantial likelihood of severe and either widespread or long-term damage to the environment being caused by those acts, reflect a growing awareness of the need to address environmental emergencies and protect the well-being of both present and future generations.[158] This could have interesting implications for the scope of R2P. Lessons learned from past tragedies serve as a reminder of the need for proactive measures to prevent catastrophic events. By exploring these complex issues, policymakers and researchers can pave the way for a more comprehensive and effective framework for environmental protection on a global scale.

[1] PhD Candidate, Nottingham Law School, Email: N1125655@my.ntu.ac.uk

[2] United Nations General Assembly, Resolution 76/300 (28 July 2022), UN Doc A/Res/76/300, p. 3.

[3] United Nations Human Rights Council, Resolution 48/13 (08 October 2021), UN Doc A/HRC/RES/48/13, p. 3.

[4] United Nations, ‘With 161 Votes in Favour, 8 Abstentions, General Assembly Adopts Landmark Resolution Recognising Clean, Healthy, Sustainable Environment as Human Right’ (United Nations, 2022) <https://press.un.org/en/2022/ga12437.doc.htm> accessed 28 June 2023.

[5] United Nations General Assembly, Resolution 76/300 (28 July 2022), UN Doc A/Res/76/300, p. 2: “Recognising that, conversely, the impacts of climate change […] interfere with the enjoyment of a clean, healthy and sustainable environment and that environmental damage has negative implications, both direct and indirect, for the effective enjoyment of all human rights”.

[6] Marc Limon, ‘United Nations recognition of the universal right to a clean, healthy and sustainable environment: An eyewitness account’ (2022) 31 Review of European, Comparative & International Environmental Law 155.

[7] ibid, p. 170. “[C]an the impacts of climate change and other environmental harms be considered a human rights violation (in strict legal terms), and would States’ obligations to promote, protect and respect the universal right to a healthy environment extend beyond their borders (i.e. would they apply extraterritorially)?”

[8] ibid.

[9] ibid.

[10] Pierre-Marie Dupuy, Droit international public [Public International Law] (6th edition, Dalloz, 2002), p. 617.

[11] ibid.

[12] ibid.

[13] Lotta Viikari, ‘Responsibility to Protect and the Environment’ in Peter Hilpod (ed) Die Schutzverantwortung (R2P) (BRILL, 2013), p. 298.

[14] Gareth Evans et al., ‘The Responsibility to Protect’ (International Commission on Intervention and State Sovereignty, 2001), p. 33.

[15] Non-exhaustive list of examples: French Charter on the Environment 2005, article 1; Costa Rican Constitution 1949, article 50; Afghan Constitution 2004, Preamble §14; Spanish Constitution 1978, article 45; Constitution of the Kingdom of Norway 1814, article 112; Constitution of the Russian Federation 1993, article 42; Palau’s Constitution 1981, article VI.

[16] César Rodríguez-Garavito, ‘A Human Right to a Healthy Environment?’ in John H. Knox and Ramin Pejan (eds) The Human Right to a Healthy Environment (Cambridge University Press, 2018), pp. 160-163.

[17] Ved P. Nanda, ‘From Paralysis in Rwanda to Bold Moves in Libya: Emergence of the Responsibility to Protect Norm under International Law – Is the International Community Ready for it?’ (2011) 34 Houston Journal of International Law 1, p. 23.

[18] Patrick Quinton-Brown, ‘Mapping Dissent: The Responsibility to Protect and Its State Critics’ (2013) 5 Global Responsibility to Protect 260, p. 264.

[19] Pierre-Marie Dupuy, Droit international public [Public International Law] (6th edition, Dalloz, 2002), p. 617.

[20] ibid.

[21] See on this issue Alex J. Bellamy, ‘A Trojan Horse?’ in Alex J. Bellamy (ed) The Responsibility to Protect: A Defense (Oxford University Press, 2014), pp. 112-132.

[22] Samantha Besson, ‘Sovereignty’ (Oxford Public International Law, 2011) <https://opil.ouplaw.com/display/10.1093/law:epil/9780199231690/law-9780199231690-e1472> accessed 30 June 2023, §50.

[23] Charter of the United Nations 1945, Articles 2§4 and 2§7.

[24] Scott Silverstone, ‘Intervention and Use of Force’ (Oxford Bibliographies, 2020) <https://www.oxfordbibliographies.com/display/document/obo-9780199743292/obo-9780199743292-0047.xml> accessed 06 September 2022.

[25] ibid.

[26] Charter of the United Nations 1945, Articles 2§4 and 2§7; Case concerning Military and Paramilitary Activities in and against Nicaragua (Nicaragua v. United States of America) (Judgement) (1984) ICJ Reports 1984, p. 435.

[27] Charter of the United Nations 1945, Article 39.

[28] ibid, Chapter VII.

[29] Christian Henderson, The Use of Force and International Law (Cambridge University Press, 2018), p. 100.

[30] Charter of the United Nations 1945, Article 27.

[31] Anders Henriksen, International Law (2nd edition, Oxford University Press, 2019), p. 259.

[32] United Nations General Assembly, Resolution 43/131 (08 December 1988), UN Doc A/RES/43/131, p. 207; Emmanuel Decaux, Droit international public [Public International Law] (3rd edition, Dalloz, 2002), p. 270.

[33] ibid.

[34] ibid.

[35] Lotta Viikari, ‘Responsibility to Protect and the Environment’ in Peter Hilpod (ed) Die Schutzverantwortung (R2P) (BRILL, 2013), p. 307.

[36] ibid.

[37] ibid.

[38] Ved P. Nanda, ‘From Paralysis in Rwanda to Bold Moves in Libya: Emergence of the Responsibility to Protect Norm under International Law – Is the International Community Ready for it?’ (2011) 34 Houston Journal of International Law 1, p. 23.

[39] Gareth Evans et al., ‘The Responsibility to Protect’ (International Commission on Intervention and State Sovereignty, 2001), p. 33.

[40] Lotta Viikari, ‘Responsibility to Protect and the Environment’ in Peter Hilpod (ed) Die Schutzverantwortung (R2P) (BRILL, 2013), p. 302.

[41] ibid.

[42] Gareth Evans et al., ‘The Responsibility to Protect’ (International Commission on Intervention and State Sovereignty, 2001), p. 17.

[43] Ved P. Nanda, ‘From Paralysis in Rwanda to Bold Moves in Libya: Emergence of the Responsibility to Protect Norm under International Law – Is the International Community Ready for it?’ (2011) 34 Houston Journal of International Law 1, p. 56.

[44] United Nations General Assembly, Resolution 60/1 (16 September 2005), UN Doc A/RES/60/1, p. 60.

[45] ibid.

[46] Ved P. Nanda, ‘From Paralysis in Rwanda to Bold Moves in Libya: Emergence of the Responsibility to Protect Norm under International Law – Is the International Community Ready for it?’ (2011) 34 Houston Journal of International Law 1, p. 56.

[47] See for instance Alex Bellamy, ‘Libya and the Responsibility to Protect: The Exception and the Norm’ (2011) 25 Ethics & International Affairs 263, p. 265. Gareth Evans et al., ‘The Responsibility to Protect’ (International Commission on Intervention and State Sovereignty, 2001), p. 33.

[48] Case concerning Military and Paramilitary Activities in and against Nicaragua (Nicaragua v. United States of America) (Judgement) (1984) ICJ Reports 1984, §242.

[49] ibid.

[50] The ICC Statute specifically addresses intentional attacks that result in long-term and severe damage to the natural environment. Such attacks are considered war crimes when the level of damage inflicted is clearly excessive compared to the anticipated military advantage. However, it is important to note that the protection of the environment, as defined by the Statute, is limited to instances of armed conflicts. Statute of the International Criminal Court 1998, Article 8(b)(iv).

[51] Gareth Evans et al., ‘The Responsibility to Protect’ (International Commission on Intervention and State Sovereignty, 2001), pp. 32-33: “In the Commission’s view, military intervention for human protection purposes is justified in […] overwhelming natural or environmental catastrophes, where the state concerned is either unwilling or unable to cope, or call for assistance, and significant loss of life is occurring or threatened”.

[52] Linda Malone et al., ‘Responsibility to Protect in Environmental Emergencies’ (2009) 103 International Law as Law 1, p. 29.

[53] Lotta Viikari, ‘Responsibility to Protect and the Environment’ in Peter Hilpod (ed) Die Schutzverantwortung (R2P) (BRILL, 2013), pp. 302-303.

[54] ibid.

[55] ibid.

[56] ibid.

[57] ibid.

[58] ibid.

[59] Which, in itself, remains a non-negligeable factor. See on this subject Riley Dunlap and Aaron McCright, ‘Organised Climate Change Denial’ in John Dryzek, Richard Norgaard and David Schloberg (eds) The Oxford Handbook of Climate Change and Society (Oxford University Press, 2011), p. 144.

[60] Examples could also be taken of the cases brought in front of the World Trade Organisation’s Dispute Settlement Body, such as the Seal Products case. See on this issue Katie Sykes, ‘Sealing animal welfare into the GATT exceptions: the international dimension of animal welfare in WTO disputes’ (2014) 13 World Trade Review 471, pp. 492-493. : “[…] one criticism that has been levelled at the EU Seals Regime is that it singles out seals for protection, even though the exploitation and killing of other animals is allowed in Europe, simply because they are ‘cute’, which would (arguably) be morally arbitrary”.

[61] Whaling in the Antarctic (Australia v. Japan, New Zealand intervening) (Judgment) (2014) ICJ Reports 2014.

[62] ibid, §25.

[63] ibid (Verbatim record 2013/18), p. 28, §19; Yoshifumi Tanaka, ‘Reflections on Locus Standi in Response to a Breach of Obligations Erga Omnes Partes: A Comparative Analysis of the Whaling in the Antarctic and South China Sea Cases’ (2018) 17 The Law and Practice of International Courts and Tribunals 527, pp. 536-537.

[64] Whaling in the Antarctic (Australia v. Japan, New Zealand intervening) (Judgment) (2014) ICJ Reports 2014, §41.

[65] Lisa Uffman-Kirsch, ‘A New Theory for Invocation of State Responsibility for Marine Environmental Harm’ (2014) SSRN Electronic Library 1, p. 50.

[66] Amy Catalinac et Gerald Chan, ‘Japan, the West, and the whaling issue: understanding the Japanese side’ (2005) 17 Japan Forum 133, p. 134.

[67] ibid; Constantinos Yiallourides, ‘Understanding Japan’s Resumption of Commercial Whaling under International Law’ in Froukje Maria Platjow and Alla Pozdnakova (eds) The Environmental Rule of Law for Oceans (Cambridge University Press, 2023), pp. 337-338.

[68] Example can be taken of the stringent problem of marine mammals’ bycatch in France and the European Union, for instance. See on this issue: Hélène Peltier et al., ‘Can modelling the drift of bycaught dolphin stranded carcasses help identify involved fisheries? An exploratory study’ (2020) 21 Global Ecology Conservation 1, p. 11.

[69] Yoshifumi Tanaka, ‘Reflections on Locus Standi in Response to a Breach of Obligations Erga Omnes Partes: A Comparative Analysis of the Whaling in the Antarctic and South China Sea Cases’ (2018) 17 The Law and Practice of International Courts and Tribunals 527, p. 548.

[70] ibid.

[71] Linda Malone, ‘Green Helmets: Eco-Intervention in the Twenty-First Century Unilateral and Multilateral Intervention’ (2009) 103 Proceedings of the Annual Meeting (American Society of International Law) 19, p. 27.

[72] Stuart Ford, ‘Is The Failure To Respond Appropriately To A Natural Disaster A Crime Against Humanity? The Responsibility To Protect And Individual Criminal Responsibility In The Aftermath Of Cyclone Nargis’ (2010) 38 Denver Journal of International Law and Policy 227, p. 243

[73] ibid.

[74] ibid. Despite the discussions surrounding crimes against humanity and the Responsibility to Protect during and after Cyclone Nargis, the actual activation of the R2P did not occur. Instead, the potential for its implementation was only contemplated by several governments. See for instance Roberta Cohen, ‘The Burma Cyclone and the Responsibility to Protect’ (Brookings Institution, 2008) <https://www.brookings.edu/articles/the-burma-cyclone-and-the-responsibility-to-protect/> accessed 30 June 2023.

[75] Stuart Ford, ‘Is The Failure To Respond Appropriately To A Natural Disaster A Crime Against Humanity? The Responsibility To Protect And Individual Criminal Responsibility In The Aftermath Of Cyclone Nargis’ (2010) 38 Denver Journal of International Law and Policy 227, p. 243.

[76] ibid.

[77] The Office of the Prosecutor, ‘Policy paper on case selection and prioritisation’ (2016, International Criminal Court) <https://www.icc-cpi.int/sites/default/files/itemsDocuments/20160915_OTP-Policy_Case-Selection_Eng.pdf> accessed 29 July 2023, §7, §40, §41,

[78] Human Rights Advocacy Collective and the ARNS Commission, ‘Informative Note to the Prosecutor – International Criminal Court pursuant to Article 15 of the ICC Statute requesting a Preliminary Examination into Incitement to Genocide and Widespread Systematic Attacks Against Indigenous Peoples by President Jair Messias Bolsonaro in Brazil’ (CADHu and ARNS, 2019), pp. 3-6; Lily Grisafi, ‘Prosecuting International Environmental Crime Committed against Indigenous Peoples in Brazil’ (2021) 5 HRLR Online 26, pp. 40-41.

[79] Lotta Viikari, ‘Responsibility to Protect and the Environment’ in Peter Hilpod (ed) Die Schutzverantwortung (R2P) (BRILL, 2013), pp. 302-303.

[80] Marc Limon, ‘United Nations recognition of the universal right to a clean, healthy and sustainable environment: An eyewitness account’ (2022) 31 Review of European, Comparative & International Environmental Law 155, p. 156.

[81] Martin Fritz and Max Koch, ‘Economic development and prosperity patterns around the world: Structural challenges for a global steady-state economy’ (2016) 38 Global Environment Change 41, p. 47.

[82] Daniel O’Neill et al., ‘A good life for all within planetary boundaries’ (2018) 1 Nature Sustainability 88, p. 92.

[83] Dinah Shelton, ‘Human Rights, Environmental Rights and the Right to Environment’ (1991) 28 Stanford Journal of International Law 103, p. 109-110.

[84] ibid.

[85] Moa De Lucia Dahlbeck, Spinoza, Ecology and International Law (2020, Routledge), p. 15.

[86] Azizan Baharuddin and Mohd Noor Musa, ‘Environmental Ethics in Islam’ in Alireza Bagheri and Khalid Alali (eds) Islam Bioethics – Current Issues and Challenges (2018, World Scientific), p. 164.

[87] Dinah Shelton, ‘Human Rights, Environmental Rights and the Right to Environment’ (1991) 28 Stanford Journal of International Law 103, p. 138.

[88] ibid.

[89] The Right to a Healthy Environment is not the only intersection between human rights and the environment. Non-environmental human rights, such as the right to life, health, and culture, have also emerged as important foundations for both human rights and environmental protection, even before the recognition of the Right to a Healthy Environment. See on this issue, Linda Hajjar Leib, ‘Theorisation of the various Human Rights approaches to environmental issues’ in Linda Hajjar Leib (ed) Human Rights and the Environment: Philosophical, Theoretical and Legal Perspective (BRILL, 2010).

[90] Maha Husain, ‘The Right to a Healthy Environment and Physical and Mental Health’ (2022, Global Network for Human Rights and the Environment) <https://gnhre.org/community/the-right-to-a-healthy-environment-and-physical-and-mental-health/> accessed 31 August 2022; Marc Limon, ‘United Nations recognition of the universal right to a clean, healthy and sustainable environment: An eyewitness account’ (2022) 31 Review of European, Comparative & International Environmental Law 155, p. 169.

[91] Declaration of the United Nations Conference on the Human Environment 1972, principle 1.

[92] United Nations General Assembly, Resolution 76/300 (28 July 2022), UN Doc A/Res/76/300, p. 3; United Nations Human Rights Council, Resolution 48/13 (08 October 2021), UN Doc A/HRC/RES/48/13, p. 3.

[93] ibid.

[94] Sara de Vido, ‘Climate change and the right to a healthy environment’ in Serena Baldin and Sara de Vido (eds) Environmental Sustainability in the European Union: Socio-Legal Perspectives (2020, EUT), p. 111.

[95] Constitution of the World Health Organisation 1946, Preamble.

[96] For example, according to the ICC Statute, when assessing the gravity of a claim, the Prosecutor must prioritise crimes such as killings, rapes, sexual or gender-based crimes, crimes against children, persecution, and acts amounting to genocide. These crimes are characterised by clear and visible physical consequences. Office of the Prosecutor, ‘Policy paper on case selection and prioritisation’ (International Criminal Court, 2016), §39.

[97] European Court of Human Rights Press Release, ‘Grand Chamber hearing on consequences of global warming on living conditions and health’ (29 March 2023) ECHR 094 (2023) <https://tinyurl.com/ECHRSwiss> accessed 19 May 2023.

[98] ibid.

[99] ibid; Imogen Foulkes and Adam Durbin, ‘Swiss court case ties human rights to climate change’ (BBC News, 2023) <https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-europe-65107800> accessed 19 May 2023.

[100] ibid.

[101] ibid.

[102] ibid.

[103] See, for instance, H.-O. Pörtner et al., ‘Summary for Policymakers’ in H.-O. Pörtner et al. (eds) Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (Cambridge University Press, 2022), pp. 8-20.

[104] Kristin Jones, ‘The Beginning of the End of Ecocide: Amending the Rome Statute to Include the Crime of Ecocide’ (2022) SSRN Electronic Library 1, p. 17.

[105] Constitution of the World Health Organisation 1946, Preamble.

[106] Samantha K. Stanley et al., ‘From anger to action: Differential impacts of eco-anxiety, eco-depression, and eco-anger on climate action and wellbeing’ (2021) 1 The Journal of Climate Change and Health 1, p. 1.

[107] ibid.

[108] Magdalena Gawrych, ‘Climate change and mental health: a review of current literature’ (2021) 56 Psychiatria Polska 903, p. 909.

[109] Christie Manning and Susan Calyton, ‘Threat to mental health with wellbeing associated with climate change’ (2018) Psychology and Climate Change 217, p. 226.

[110] Glenn Albrecht, ‘Solastalgia. A New Concept in Health and Identity’ (2005) 3 Philosophy, Activism, Nature 41, p. 41; Lindsay Galway et al., ‘Mapping the Solastalgia Literature: A Scoping Review Study’ (2019) 16 International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 1, p. 5.

[111] Christie Manning and Susan Calyton, ‘Threat to mental health with wellbeing associated with climate change’ (2018) Psychology and Climate Change 217, p. 225.

[112] Kuok Ho Daniel Tang, ‘Climate Change and Its Impacts on Mental Wellbeing’ (2021) 3 Global Academic Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences 144, p. 145.

[113] Ritu Bharadwaj, N. Karthikeyan and Ira Deulgaonkar, ‘Urgent preventative action for climate-related suicides in rural India’ (2023) 2023 IIED Briefing 1, p. 2.

[114] American Psychiatric Association, ‘DSM-5 Fact Sheets’ (American Psychiatric Association, 2023) <https://www.psychiatry.org/psychiatrists/practice/dsm/educational-resources/dsm-5-fact-sheets> accessed 30 June 2023; World Health Organisation, ‘International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems 10th Revision’ (World Health Organisation, 2019) <https://icd.who.int/browse10/2019/en> accessed 30 June 2023.

[115] Glenn Albrecht, ‘Solastalgia. A New Concept in Health and Identity’ (2005) 3 Philosophy, Activism, Nature 41, p. 41

[116] Christie Manning and Susan Calyton, ‘Threat to mental health with wellbeing associated with climate change’ (2018) Psychology and Climate Change 217, p. 234; Yumiko Coffey et al., ‘Understanding Eco-Anxiety: A Systematic Scoping Review of Current Literature and Identified Knowledge Gaps’ (2021) 3 The Journal of Climate Change and Health 1, p. 5.

[117] ibid.

[118] See for example the Sea Shepherd organisation when they declare: “We fight to preserve the planet because we recognise that we share the Earth with other species and that their well-being is inexorably linked to ours.”. Peter Hammarstedt, ‘Our Mission – Protect Marine Habitat’ (Sea Shepherd Global, 2023) <https://www.seashepherdglobal.org/who-we-are/our-mission/> accessed 20 February 2023

[119] Gareth Evans et al., ‘The Responsibility to Protect’ (International Commission on Intervention and State Sovereignty, 2001), p. 33.

[120] Statute of the International Criminal Court 1998, Articles 6, 7, 8 and 8(bis).

[121] Statute of the International Criminal Court 1998, Article 7(1).

[122] ibid.

[123] ibid, Article 7(1)(k).

[124] Statute of the International Criminal Court 1998, Article 7(1).

[125] International Criminal Court, ‘Elements of Crime’ (2013, ICC), Article 7(1)(k).

[126] Statute of the International Criminal Court 1998, Article 7(2)(a).

[127] ibid.

[128] ibid, Article 7(1)(k).

[129] International Criminal Court, ‘Elements of Crime’ (2013, ICC), Article 7(1)(k).

[130] Lotta Viikari, ‘Responsibility to Protect and the Environment’ in Peter Hilpod (ed) Die Schutzverantwortung (R2P) (BRILL, 2013), p. 302.

[131] ibid.

[132] For example, according to the ICC Statute, when assessing the gravity of a claim, the Prosecutor must prioritize crimes such as killings, rapes, sexual or gender-based crimes, crimes against children, persecution, and acts amounting to genocide. These crimes are characterised by clear and visible physical consequences. Office of the Prosecutor, ‘Policy paper on case selection and prioritisation’ (International Criminal Court, 2016), §39.

[133] This example is reminiscent of the 2019 wildfires impacting the Amazonian forest, giving rise to new debates around ecological interventionism. See on this subject Simon Petite, ‘Droit d’ingérence écologique en Amazonie’ [A right to ecological interventionism in Amazonia] (Le Temps, 2019) <https://www.letemps.ch/monde/droit-dingerence-ecologique-amazonie> accessed 17 May 2022.

[134] Gareth Evans et al., ‘The Responsibility to Protect’ (International Commission on Intervention and State Sovereignty, 2001), p. 33.

[135] Ved P. Nanda, ‘From Paralysis in Rwanda to Bold Moves in Libya: Emergence of the Responsibility to Protect Norm under International Law – Is the International Community Ready for it?’ (2011) 34 Houston Journal of International Law 1, p. 56.

[136] AFP, ‘Incendies en Amazonie : Jair Bolsonaro, sous le feu des critiques, reproche à Emmanuel Macron une mentalité colonialiste’ [Fires in the Amazon: Jair Bolsonaro, under fire from critics, accuses Emmanuel Macron of a colonialist mentality] (FranceInfo, 2019) <https://www.francetvinfo.fr/monde/bresil/incendies-en-amazonie-jair-bolsonaro-sous-le-feu-des-critiques-internationales-reproche-a-emmanuel-macron-une-mentalite-colonialiste_3587283.html> accessed 17 May 2022.

[137] ibid.

[138] ibid.

[139] See for instance Laurence Teillet, ‘L’interventionnisme écologique en droit international de l’environnement’ [Ecological Interventionism in International Environmental Law] (2022) Aurore 1.

[140] Simon Petite, ‘Droit d’ingérence écologique en Amazonie’ [A right to ecological interventionism in Amazonia] (Le Temps, 2019) <https://www.letemps.ch/monde/droit-dingerence-ecologique-amazonie> accessed 17 May 2022.

[141] International Panel of Eminent Personalities, ‘Report on the 1994 Genocide in Rwanda and Surrounding Events’ (2001) 40 International Legal Materials 141, p. 157.

[142] Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica, ‘Rwanda genocide of 1994’ (Britannica, 2023) <https://www.britannica.com/event/Rwanda-genocide-of-1994> accessed 29 June 2023.

[143] ibid.

[144] ibid.

[145] ibid.

[146] Ved P. Nanda, ‘From Paralysis in Rwanda to Bold Moves in Libya: Emergence of the Responsibility to Protect Norm under International Law – Is the International Community Ready for it?’ (2011) 34 Houston Journal of International Law 1, p. 23.

[147] United Nations Human Rights Council, Resolution 48/13 (08 October 2021), UN Doc A/HRC/RES/48/13, p. 3; United Nations General Assembly, Resolution 76/300 (28 July 2022), UN Doc A/Res/76/300, p. 3.

[148] Constitution of the World Health Organisation 1946, Preamble.

[149] H.-O. Pörtner et al., ‘Summary for Policymakers’ in H.-O. Pörtner et al. (eds) Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (Cambridge University Press, 2022), pp. 8-20.

[150] Samantha K. Stanley et al., ‘From anger to action: Differential impacts of eco-anxiety, eco-depression, and eco-anger on climate action and wellbeing’ (2021) 1 The Journal of Climate Change and Health 1, p. 1.

[151] Ritu Bharadwaj, N. Karthikeyan and Ira Deulgaonkar, ‘Urgent preventative action for climate-related suicides in rural India’ (2023) 2023 IIED Briefing 1, p. 2.

[152] Statute of the International Criminal Court 1998, Article 7(1)(k).

[153] Human Rights Advocacy Collective and the ARNS Commission, ‘Informative Note to the Prosecutor – International Criminal Court pursuant to Article 15 of the Rome Statute requesting a Preliminary Examination into Incitement to Genocide and Widespread Systematic Attacks Against Indigenous Peoples by President Jair Messias Bolsonaro in Brazil’ (CADHu and ARNS, 2019), pp. 3-6.

[154] Gareth Evans et al., ‘The Responsibility to Protect’ (International Commission on Intervention and State Sovereignty, 2001), p. 33.

[155] Statute of the International Criminal Court 1998, Article 7(1)(k).

[156] Liana Georgieva Minkova, ‘The Fifth International Crime: Reflections on the Definition of Ecocide’ (2023) 25 Journal of Genocide Research 1, p. 74.

[157] Edwin Zaccai, ‘Over two decades in pursuit of sustainable development: Influence, transformations, limits’ (2012) 1 Environmental Development 79, p. 87.

[158] Stop Ecocide International, ‘Legal Definition of Ecocide’ (Stop Ecocide International, 2021) <https://www.stopecocide.earth/legal-definition> accessed 29 July 2023; Abhijeet Shrivastava, ‘Forestalling the Responsibility to Protect Against Ecocide’ (2022, Völkerrechtsblog) <https://voelkerrechtsblog.org/forestalling-the-responsibility-to-protect-against-ecocide/> accessed 30 June 2023.